21 May The power and pitfalls of human stories

Human-centric stories can be incredibly compelling and inspire people to take action, but when exploring them we must ensure we are not inadvertently contributing to the very issues we are documenting and seek to address.

Stories are what human culture is built on. First, they were oral, then visual, and finally written. The most powerful stories are those that immerse us in the world being woven by the author – where we become somehow intertwined with the reality being recounted to us. To achieve this, as the work of Joseph Campbell testifies, many stories have a protagonist – a ‘hero’ – who goes on a journey, oftentimes facing adversity they must overcome.

This approach to taking people on a journey within fictional stories is just as relevant to non-fiction. Providing a human dimension by exploring the experience of one person or a group of people in relation to a particular issue makes the seemingly intangible, unrelatable, and inaccessible, become more tangible, more relatable, and more accessible.

When it comes to engaging an audience on a particular topic giving stories a human face can therefore help amplify their impact. Research shows that stories that are character-driven and emotionally and personally compelling releases oxytocin, and engages more of our brain than when we are exposed to facts.

Think of the last documentary film or image to burn itself into your subconscious, and the emotions they triggered within you. The images which stay with us the longest are often those of our fellow human beings – such as ‘napalm girl’, Phan Thị Kim Phúc, or the solitary corpse of Syrian toddler, Alan Kurdi, washed up on a beach in Greece.

Giving a human dimension to an issue – be it the war in Ukraine, the impact of Covid, or the consequences of the recent floods, wildfires, and droughts that have ravaged many parts of the globe – triggers an emotional response within people. If, as documentary storytellers, we want to engage people on a particular subject it would therefore make sense that we are likely to have the greatest impact if we tell a human story. That being said, the emotional response is but a spark and shouldn’t be confused for the fire that is actually needed for meaningful behavioural and cultural change.

Consider the consequences the absence of human stories within visual and general communication has had on engagement around the issue of climate change. For decades most visual communication has centred around animals – such as starving polar bears, and, more recently, animals killed or injured by wildfires. If not animals, then the wider natural world is represented – such as melting icecaps or the destruction caused by extreme weather events. Human stories – particularly those showing the impact climate change has been having on communities for decades – have been severely lacking.

This has meant that climate change has largely been framed as an environmental issue, when in fact it is so much more. It’s a human rights issue, a women’s rights issue, a social and economic issue, a food and water security issue, a health issue – the list goes on. Yet, for over 30 years, we’ve largely only seen images that capture the ongoing impact on the natural world around us – not on human communities, cultures, and systems.

We should never stop documenting the impact we’re having on non-human life – they are incredibly important images – but the absence of human-centric stories on issues such as climate change and biodiversity loss, which have a greater power to compel an audience to take action, will have invariably hampered meaningful engagement and a deeper understanding of the issues and their root causes. This is being acknowledged more and more – in relation to climate change at least – and a shift is occurring, albeit slowly, to exploring more human-centric stories as a means to affect meaningful engagement and behaviour change.

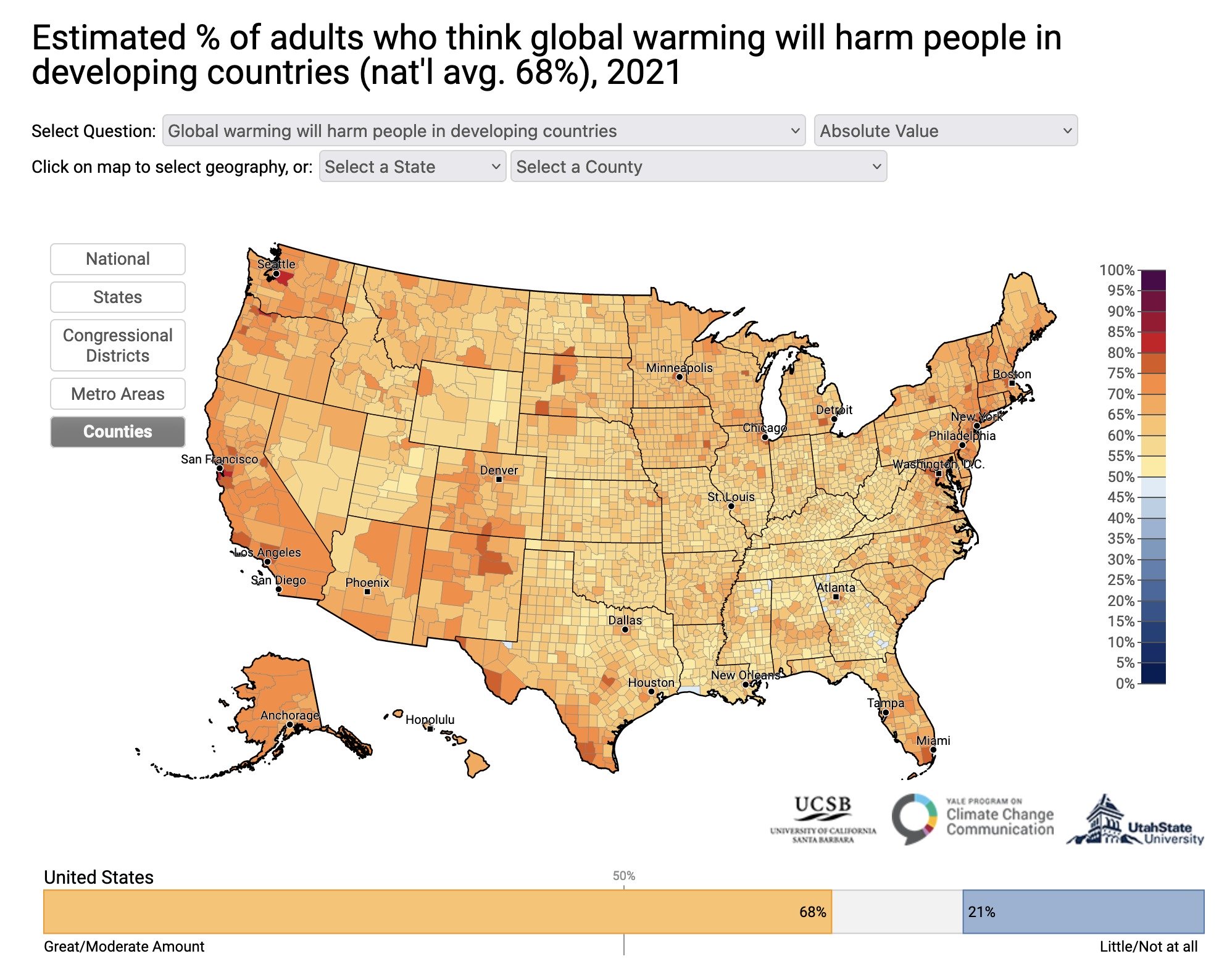

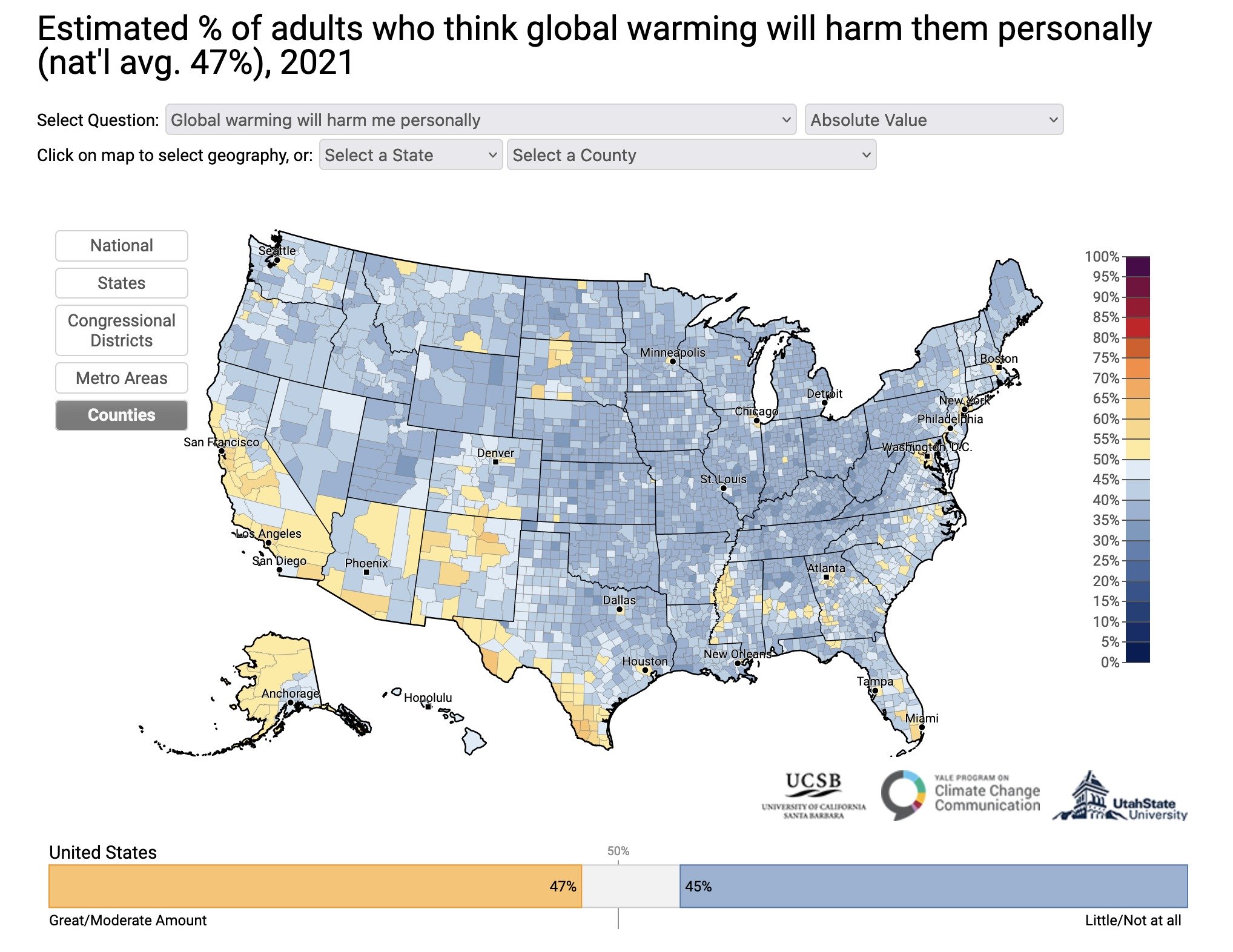

It’s important to understand that further distortions can be created by simply going to hotspots. A person in the US constantly being exposed to stories of people suffering in Bangladesh due to flooding, the Maldives due to rising tides, and India due to droughts might retain a belief that the issue remains distant geographically. Each year Yale University in the US conducts a survey that reveals this very phenomenon. This is despite the country itself being ravaged more and more by wildfires, droughts, floods, and coastal erosion – the increasing frequency and intensity of which is a direct consequence of anthropogenic climate change.

This feeds into the broader, deeper issue of representation. The emotions elicited by a human story can have, depending on how the person or people are represented, positive or negative consequences. They can be used to challenge existing ideas, narratives, or systems, or used to reinforce them. An aspect of this is the capacity for certain images to maintain a stereotype – the use of an emaciated child from sub-Saharan Africa as a victim of famine and symbol of absolute poverty is but one example – which can do more harm than good, not least by nurturing a sense of otherness. Such an image generates the intended response of increasing short-term support for a cause, but at the same time helps to maintain a certain perception of sub-Saharan Africa and its people. The repeated exposure to such a visual narrative generates the perception, if it goes unchallenged, that it’s somehow fated – that ‘it’s just the way it is’. This in turn hinders any real attempt by the audience to gain anything but the most superficial understanding of why the issue is occurring – or reoccurring.

The use of an emaciated child to represent famine in countries on the African continent has been going on for decades – the disturbing image by Kevin Carter of a Sudanese child being watched by a nearby vulture as she struggles desperately to crawl to a food centre, being one of the most infamous – but what have they done to deepen people’s understanding of the underlying causes? An ill-considered approach to a human story can contribute to the root causes of the issues we are documenting by sustaining the prevailing, deep narratives used to engineer them.

More broadly speaking, as way of an example, if people in the Global North constantly seek out stories and images of people in far-off lands, i.e., the Global South, to then share them with audiences in the Global North, they run the risk of perpetuating the narratives that have been maintained since the birth of photography – the reductionist and occidental perception of the world around them and the othering and exoticisation of people from other parts of the world – all of which have been built on the foundations of a colonial mindset. It’s this mindset that is ultimately a root cause of so many of the environmental and social issues and injustices that exist today.

They who control the tools of storytelling control the narrative. This situation both represents and maintains the power imbalance that has existed for so long and is rooted in a colonial mindset.

The lack of diversity that has existed in the stories being told and the people telling the stories – a result of historical and ongoing injustices – has played a critical role in maintaining deep, destructive narratives. It is the absence of this plurality – particularly of stories crafted by people from within the communities themselves – that creates this ‘outsider’s dilemma’ that every documentary storyteller should be grappling with – ‘Am I the best person to tell this story?’ or ‘Am I the right person to tell this story?’

In a situation where you are one of the only visual storytellers looking at an issue, the answer could be both yes and no. There will be people from within the community who could offer a deeper, more comprehensive representation, but if they do not have the tools and the means to tell the story through their eyes at that moment in time, what then?

Nurturing collaboration by building relationships within the community you wish to document, and spending time with them, rather than approaching things in the all-too-typical extractive manner, might be the best means of getting the most accurate representation of the issue we can at the time. But really, we need to get cameras into the hands of more people within under-represented communities so that there is no longer a dependency on an outsider to represent them and the challenges they face, and to ensure that the visual representation of critical issues is carried out from a diversity of perspectives. This will take time and requires systemic change in order to address the injustices within wider society that maintain existing power imbalances, but is also something we can strive to achieve within the visual storytelling community.

A variety of perspectives on an issue is vitally important for addressing inherent biases and prejudices. An outsider documenting the experiences of a community is not inherently a bad thing – ultimately all communities, cultures and societies are interconnected, and so we all, to a lesser or greater extent, play a role in a given issue. The globalised nature of the impact and influence of industrial, capitalistic society means that an event, no matter how seemingly insignificant, anywhere in the world has consequences for us all – whether we are aware of them or not. Whether it’s buying cheap clothing and the collapse of a clothing factory in Bangladesh, or buying cheap meat and a global pandemic – our choices individually and collectively have consequences.

When we do go into communities of which we are not a part, we must go in not only with good intentions but, most importantly, a considered approach to power imbalances and representation, so as not to sustain deep, destructive narratives.

Those in a position of privilege – be it between countries or within a country, regardless of gender, religious beliefs, economic status, or skin colour – must be aware of the power imbalances and the destructive legacies that have been created and sustained by their cultures, and put measures in place to minimise the potential harm their work might cause, and maximise its positive impact.

Our responsibility as documentary storytellers is not to try and share an objective truth – there is no such thing – but instead to represent the people we document in a way that is sensitive and respectful of their beliefs and wishes. We can only do that if we build relationships with them and include them in the storytelling process from start to finish. This is a lot more work, and takes a lot more time, but if we truly want to have a positive impact on the lives of the people we document, and the issues we explore, then we must embrace this process and incorporate it into our practice.

Much like the climate itself, where the possibility exists that the beating of a butterfly’s wings in one part of the world might play a role in the creation of a storm on the other side of the world, the complexity and interconnectedness of our global society is such that we can’t know the impact of what might otherwise be perceived as insignificant within our own community. So, knowing this, we should all be working to maintain a high standard of ethics – we must be the change we want to see.

If our desire as documentary storytellers is to have an impact – for our work to inform and inspire action, we need to consider how best we can go about doing that. Oftentimes it will mean exploring a human story. However, in exploring a human story, we must consider how we represent both the people and the story so as not to do more harm than good. Being a documentary storyteller offers an incredible opportunity to explore the fabric of our societies, but if we wish to be agents of genuine, positive change – and we have an incredible potential to be exactly that – then we must tread carefully so as not to perpetuate the very narratives which have created the injustices and issues we seek to ameliorate.

////

Chris King

I have studied sustainable development and carried out related work using participatory methods. Being from Northern Ireland, I also have first-hand experience of the impact of a colonial mindset on individuals and communities and their representation. This piece is informed by these experiences, and many others, and has also been inspired by my conversations with the documentary storytellers I’ve interviewed for the Documentary Storytellers podcast – all of whom are seeking to approach their work in a conscious and sensitive manner, and striving to maximise the positive impact of their work. This is my first time articulating these thoughts and feelings in writing, and I hope with time I will gain both deeper insight and the vocabulary to be able to discuss and engage people on the need to decolonise visual storytelling more effectively. This is the first step on that journey. Thank you for taking the time to read this article, and if you have anything you would like to share, challenge, or feedback on, please do get in touch via email – [email protected]